DAY 22 – MARCH FOCUS ON NORFOLK ISLAND’S REEF

Two corals. Both very different.

My March focus on Norfolk Island’s reef could almost go on for a full year, there’s so much to write about.* But time dictates, so I will confine my efforts to one concentrated effort of randomness! Randomness, because there has been no plan to my posts. They have evolved as the month has progressed and as my fancy has taken me.

This March focus is my marine equivalent of NaNoWriMo (‘a fun seat-of-your-pants approach to creative writing’ where you aim to write 50,000 words during the month of November), hence my title for today’s post. Charles Dickens loved a good short story!

Anyway, like many a good novel’s plot, I digress. Today is indeed a short story, highlighting two very different corals commonly seen, but not necessarily common, in our bays:

the sea mat, Palythoa tuberculosa

and the hammer coral, Fimbriaphyllia ancora.

As you read this, bear in mind that corals are animals. For no reason other than it is an amazing and wonderful fact!

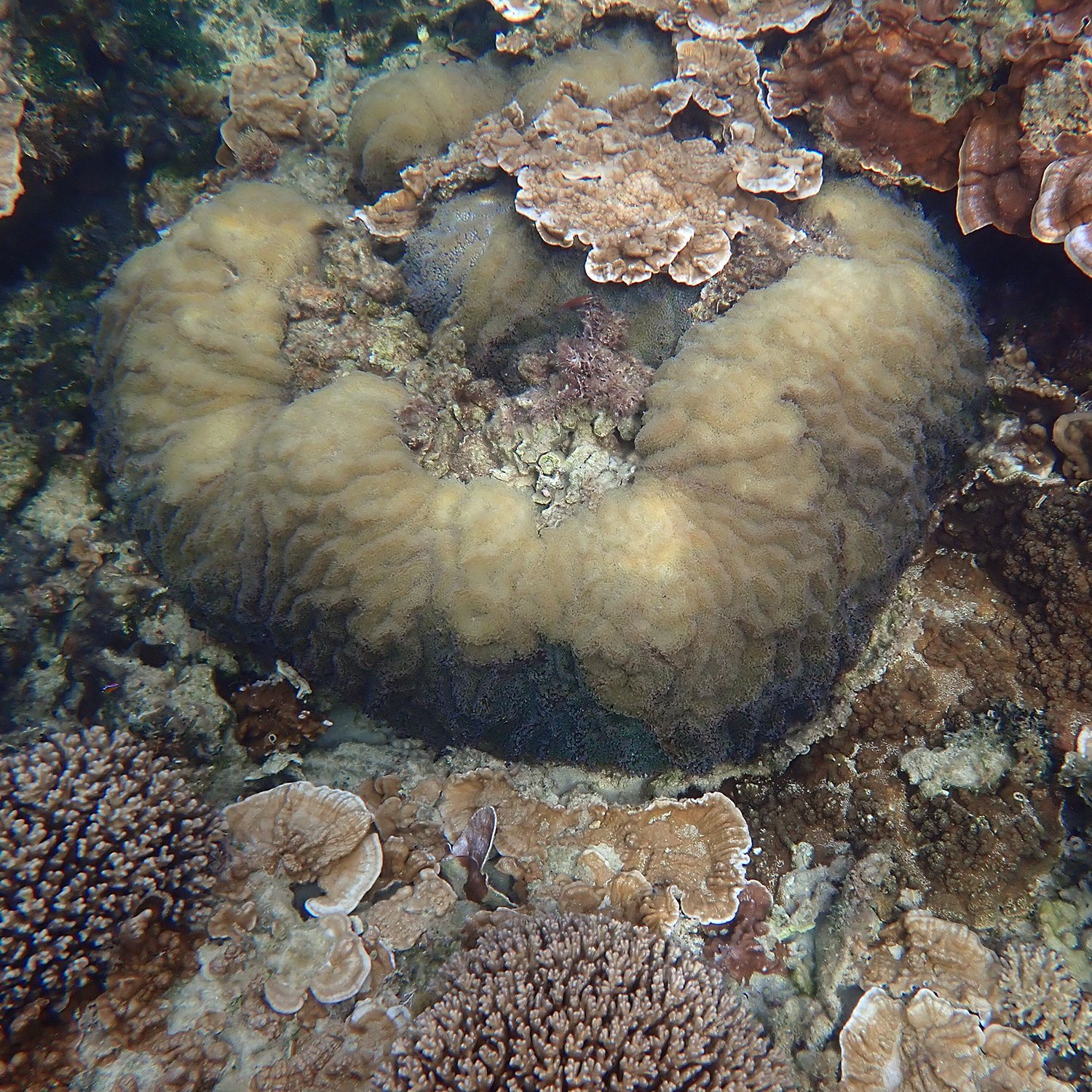

The seat mat

This coral is a zoanthid, or a soft coral, and looks just like its name – a rubbery encrusting cushion. From pale beiges, to limey greens and the deepest of yellows, the individual coral polyps are all set into the common tissue base, or gelatinous framework (called a coenenchyma). Each polyp is slightly raised from the base, with a ring of tentacles in two rows. They are well suited to their preferred habitat where the waves break over the reef, because they hug the substrate (the base on which they are growing) so tightly.

When their mouths are closed, they have a puckered appearance (bottom right in the photos below).

As it is a soft coral, it has eight tentacles or multiples of eight. For the record, hard corals have six or multiples of six.

One thing worth noting about sea mats is the toxic mucous they exude called palytoxin (Wikipedia). You mustn’t get this in an open wound, in your eyes, or ingest it in anyway. It isn’t the coral itself that produces this, but rather by a bacteria that lives symbiotically with the polyps. It can cause numbness, hallucinations or even death. Interestingly, indigenous Hawaiians would use the poison from a relative of this coral, Palythoa toxica, on the tips of their spears.

So:

Don’t step on them.

Don’t touch them.

The hammer coral

These are easily spotted because of their waving tentacles with little ‘hammers’ or anchors on the tips. Some of the ones we have here look like they have little miniature feet on the ends. Whatever they look like to you, run with it! It’s open to your interpretation!

The tentacles have stinging cells (nematocysts) that allow them to defend their space. (You can check out my post War of the Coral Worlds for more on this space-claiming behaviour.)

Hammer coral is a hard coral, with six tentacles or multiples of six. When these are retracted, the skeleton beneath can be seen (bottom left).

While hammer coral is common in some locations – we have quite a few colonies here, for example – they are listed as vulnerable under the IUCN’s Red List, although interestingly Norfolk Island is not included on their geographic range map, but Lord Howe is. The forgotten reef, yet again!

The reason it is listed as vulnerable is because it is threatened by poor water quality around coral reef habitats, climate change, and it is often targeted by the live aquarium trade because of a characteristic of some hammer corals to take up bioluminescent algae – that is, they glow in the dark and under some lights.

*I’ll still be bringing you posts, just not every day!