We are on track to have the wettest year on record since 1890, when records officially began here on Norfolk Island. In 1893 the annual rainfall was 1962.7 mm, and in 1998 we had 1988.2 mm. So far this year (January through to the end of November) we have had 1866 mm. Add to this the rainfall since 1 December, and with wet weather forecast for next week, and it will mean we should break that record easily.

To put this into context, our average mean annual rainfall since 1890 is 1282.4 mm. Readers up and down the east coast of Australia will all understand what an unusual year it has been.

Lovely rain. Who doesn’t love a good drenching? I think we can all agree that we are entirely dependent on these rains to survive and to replenish our depleted water table. It isn’t that long since we were sucking dust from the bottom of our tanks and air from our bores, while relying on the Australian Army’s desalination plant to help out in what became a very dire situation indeed.

Managing the rain

But this abundant rainfall can be problematic as well. In fact, it has brought into sharp focus what we are doing to our environment. The extra water that is not caught in our tanks and dams is laden with our precious soils and is nutrient rich with nitrates and phosphates introduced by our land-management practices and from our wastewater systems. It runs down our creeks and out to sea.

Corals dislike fresh water. They dislike fresh, nutrient-rich water laden with sediment even more. Since 1789, when Lieutenant Philip Gidley King had the first channel cut through Kingston to drain the swamp for agriculture, we have been directing fresh water onto our corals. Before that, water would pool in the swamp, blocked by the rock wall that once stretched from the lime kiln to Chimney Hill, which has since been quarried. Most of the time it would gradually flow out to sea from under the sand, or evaporate. Since the 1960s at least, it has been widely reported that the water flowing out the channel into Emily Bay is having a detrimental effect on the reef. Consequently, our reef is now in a sorry state.

The above images of Kingston and Emily Bay were taken on 6 February 2022

Listen to the experts

Dr Tracy Ainsworth, a coral expert and associate professor at the University of NSW, has been visiting the island to undertake research for Australian Marine Parks for nearly three years now. She says (as reported in the Sydney Morning Herald on 20 November 2022): ‘the rate of diseased coral in Norfolk Island’s lagoonal reef [i]s now among the highest recorded on an Australian reef.’

Yes. It is among the highest recorded on an Australian reef. And Australia has a lot of reefs!

The extent of this disease she is referring to is a direct result of the runoff from Kingston into the lagoon.

What makes this even more concerning is what we stand to lose. Professor Andrew Baird, chief investigator in the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, also quoted in the same SMH article ‘estimates that at least 30 per cent of the species … documented on Norfolk Island are undescribed, thus unknown to science.’ In other words, a third of our corals could be unique, and the way we are going we could lose them before we even understand what we have. As I have said before on these pages, if around 30 per cent of your corals are as yet undescribed, as in, new to science, then not moving heaven and earth to save them is tantamount to burning the library before you know what is on the shelves, isn’t it?

What are we going to do with Doris?

Many of you will have read about the rescued green sea turtle, Doris. With the help of an amazing team of people, she is steadily gaining weight and gradually overcoming the infections caused by the poor water quality of her home in Emily and Slaughter Bays. To be brutally honest, the resources put into her care and recovery, while provided willingly by many individuals and organisations, have been huge for a small community. She is still young and has a lot of living to do. Hopefully in the new year she will be well enough to return to the wild.

But tell me this: where are we going to release her? Into the same environment that made her sick in the first place?

An emaciated Doris, covered with algae

The role of Council

Back in April of this year, Norfolk Island Regional Council issued a media release that talked about water quality, and raised the issue of septic tanks and soakage trenches on the island. Because some readers may not have seen this, I have included the relevant sections here. This is what they said, verbatim:

It is well known that the impact of human activity on the island poorly placed and managed septic tanks, is having a detrimental impact on the receiving environment. The high nutrient loads from soakage trenches and livestock is now severely degrading the reef in Emily Bay which is showing signs of significant coral death and algae growth. Faecal contamination from these sources also poses a risk to human health, with swimmers and other bay users exposed to the risk of infection during run-off events.

In other words, our management of our personal waste is not good enough. Because of this, Council has changed the planning requirements for new tanks:

The new [Water Resources Development Control Plan] DCP has a much more stringent approval process for new developments than previously required on Norfolk Island with the aim to bring the island in line with best practice, to ensure better environmental outcomes, and reduce public health risks to the community.

Existing developments are required to seek approval to ensure future work is as compliant as practicable with the new DCP. The main focus of these approvals will be the distance of effluent disposal areas to waterways and groundwater bores and to ensure that traditional adsorption trenches are no longer constructed.

If a trench is going to be used for the dispersal of effluent, it must be an evapotranspiration trench. These are much shallower and dispose of wastewater through evaporation from the soil surface and transpiration by plants, without discharging wastewater to the surface water or groundwater aquifer.

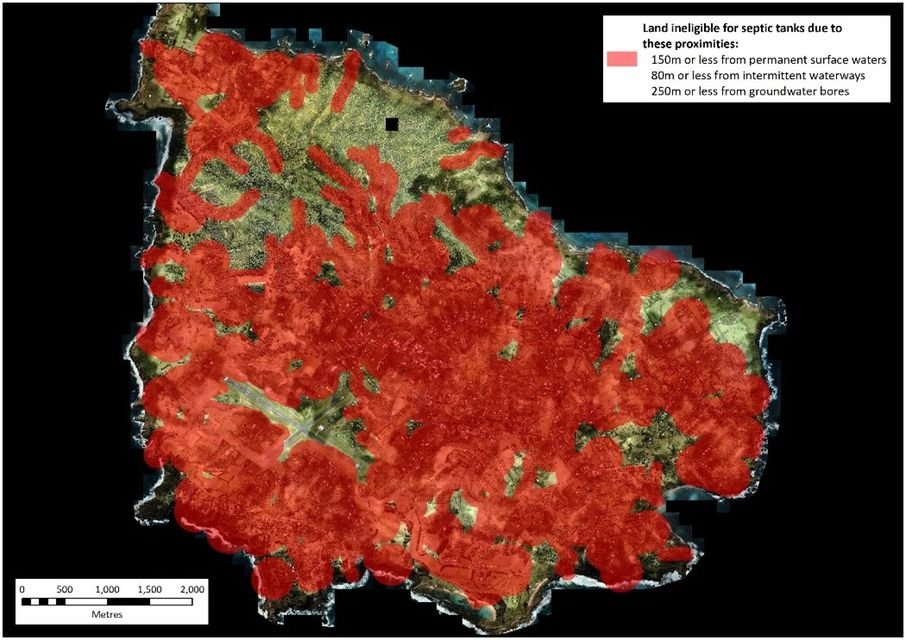

From the NIRC media release (my emphasis): ‘The above image shows in red the areas of the island where a septic tank would be prohibited under NSW environmental standards with consideration only to distances from waterways and groundwater bores. The figure alone highlights the need for change.’

In the image above, the red areas represent all the areas of the island where it would be prohibited to install soakage trenches under New South Wales environmental standards. I do wonder, if it is not OK in Australia, why has it been OK to allow them here with little in the way of planning controls in place? But the fact of the matter is we do have them and now we have to clean them up. Many businesses and homes are, probably unwittingly, leaching effluent into our porous soils, which is then trickling downhill and into our surrounding seas, to the detriment of the wildlife there. Unfortunately, where there are existing septic tanks and soakage trenches, Council, our marine wildlife and its environment are relying on island residents to do the right thing by maintaining them properly. I appreciate that this is a legacy issue, but it is high time we grasped the nettle and fixed this.

For individuals and businesses on the island, the cost of replacing these out-dated septic systems with enclosed systems that would also provide potable water for the vegetable garden and fruit trees (in case that drought comes back, which, no doubt, it will) is double what it would cost in Australia. The combined cost of freight plus the waste management fees levied by Council on imported goods to the island make it prohibitively expensive. Realistically, we can’t expect the urgent action we need without some assistance or incentives, whether that is in the form of interest-free loans; waived waste-management levies and/or freight costs; a reduction in rates for those who are prepared to update their infrastructure; the bulk purchase of new systems to obtain better prices; and so on.

What can individuals do right now?

In the meantime, what can we do right now? Here I’m going to quote Norfolk Islander Natalie Grube. This is a segment from her piece on the Norfolk Wave campaign website:

Understand that everything that we pour down our sinks and flush down our toilets enters our marine environment one way or another. Our soils are very porous and will carry surface water into our groundwater systems, which then leach out into the ocean.

Find out when your septic tank was last pumped out. This should occur every three months at a minimum to ensure that the waste water isn’t joining the groundwater system. Most people wait until their septic is smelly, though this means you have waited far too long! If you haven't pumped out your septic tank in a long time, and you still can't smell it - then the contents are most likely leaching out into the groundwater.

Decommission your septic trench if you have one! They are not designed to be used anywhere near a waterway ... which is ... everywhere on Norfolk!

Use environmentally friendly cleaning products. Read the labels and ask questions! Nag your suppliers and tell your friends!

Choose your agricultural chemicals wisely and use them sparingly. When we have heavy rainfall the runoff will carry these contaminants into the marine environment either directly or via the groundwater.

Plant natives and protect areas of native vegetation. This helps to preserve biodiversity, which in turn creates healthy ecosystems that clean the water, purify the air, maintain healthy soil and regulate the climate.

We need help

The situation is critical and we have no time to lose. And while we all need to take responsibility for our private infrastructure, we also need help. This problem is simply too big for a small population of 2,200 people to fix.

We need:

the anomalies around Norfolk Island’s legislation to be amended in order to ensure our environment has all the protections and assistance it needs

transparent water-quality monitoring for both reef health and human health, with the results published and available to the general public

all wastewater infrastructure, private and public, brought up to 21st century standards, island-wide, with consideration given to the incentives and assistance outlined above

to put a dollar value on Norfolk Island’s reef, in terms of its amenity to the residents and visitors to the island, its value to the tourism sector, its association with a World Heritage area, let alone its broader significance as a unique ecosystem

to immediately prevent polluted water being allowed to run directly into our lagoons and onto our coral reef (and this doesn’t mean letting polluted water sit around the foundations of a significant World Heritage Convict Site either)

a public education programme around the use of cleaning products, agricultural chemicals, septic systems, etc

If we don’t act fast, we will be responsible for the loss of an incredibly special ecosystem.

Now look Doris in the eye and tell her she is just one turtle.

#BeforeItsGone #COP15 #operationdoris #Doris #waterquality #environment #coralreef #theforgottenreef