Paragoniastrea australensis, one of the stony corals, is also known as a brain coral or the lesser star coral. Each colony is covered in its own unique and intricate maze. I could stare at them for hours! Such is my enthusiasm for this particular coral, if you do a Google search for images of this species, you will find my photos plastered all over the web, thanks to their having been disseminated via iNaturalist! You will find the colour range astonishing.

It is an incredibly slow growing species, with rates recorded at Peel Island, off Brisbane, Queensland, at a mean average of 5.6 mm a year (see the screenshot from the Coral Trait Database, below). The relatively modest specimen featured in this post measures more than 600 mm across. Bearing in mind that the water is a little cooler here compared with Brisbane, the growth rate could be actually slower than that, but let’s be conservative and say 5.6 mm a year and the coral size at 600 mm wide. That makes this coral more than 100 years old (107, if you want to be pedantic).

In January, I spotted this little coral in a quiet corner of Emily Bay. It is close to another coral colony, a different species, that suffers from rampant coral ‘cancer’, but that is a topic for another day. Here on Norfolk Island's reef, coral disease in stony (or boulder) corals is not as common as it is in the montipora corals. When it strikes, it moves more slowly in these boulder corals than it does in those other species.

The photos below record the progress of the disease, believed by the coral health researchers to be blackline disease, from 12 January 2024 (top left) when I first chanced upon it, to 6 April 2024 (bottom right). It may progress more slowly, but it is still just as destructive; as the coral tissue dies, oportunisitc algae colonises the skeleton. What we are left with is a boulder with a small amount of living tissue at the top and the rest is dead. Gone.

That is 100 years of growth. In less than 100 days.

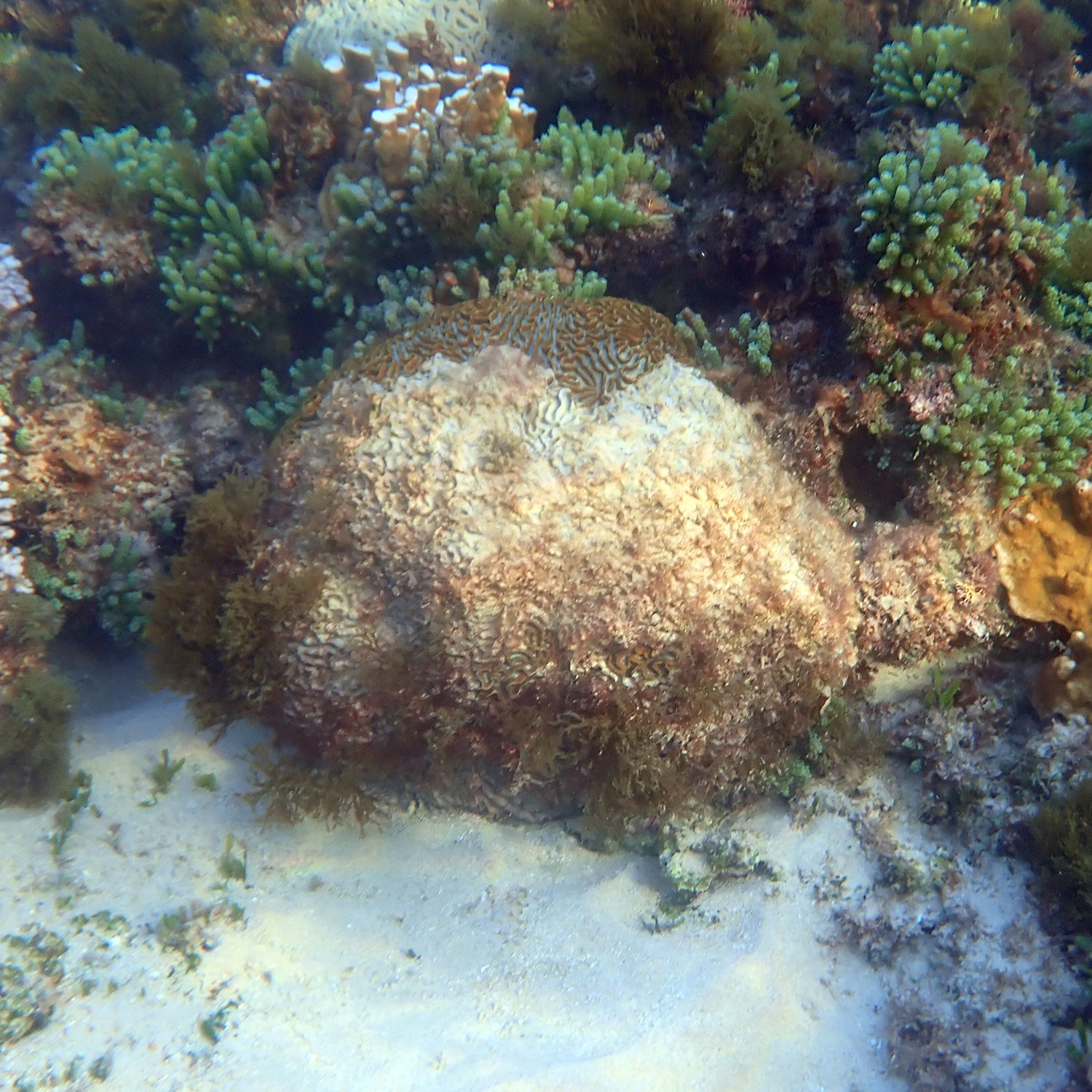

This is just one example of what is happening around Norfolk Island’s inshore reef. Slowly, inexorably, we lose a colony here, and another there. I can’t help but wonder what would happen if this disease got hold of one of our really large Paragoniastrea australensis colonies, such as the one in the photo, below, which, incidentally, is not very far from the one featured in the photos above. I wrote about this beauty in a blog post back on 20 March 2022.

So what is causing this disease? According to the many reports and studies (which I’ve covered extensively in this blog), it is thought that the poor water quality flowing into our lagoons is the culprit. Check out the Further Reading at the bottom of this page.

We’ve got to clean up our act if we want to give this ecosystem a chance of surviving whatever is coming at it in future years. It is as simple as that.

I wrote about this massive coral in a blog post ‘The Ancient Massives’, 20 March 2022

Growth rates for Paragoniastrea australensis (Coral Trait Database)

Further reading: