Sea hares, little submarine shreks that lumber their way slowly around the shallows of our coral reef lagoons are, I think, rather fascinating. And they are actually very common, although most people won’t have heard of them. They get their name from the two rhinophores (sensory tentacles) that have the appearance of rabbit ears on their heads.

We have a few different species of sea hares here on Norfolk Island; you can check them out on the nudibranchs, sea hares, flat worms and ribbon worms page of this website. The most common is the white-speckled sea hare, Aplysia argus, which is native to the Indo-Pacific region.

You are what you eat!

You can see in the photos below, their colour can vary widely depending on what algae they are snacking on. Different algae have different colours, and it is this that determines their colour. It also means they can blend in nicely with their background. Handy when you want to evade detection.

Quick facts

Sea hares disappear from the beginning of spring for a few months over summer, but by the autumn they appear once more. Having said that, I’ve already seen a couple of lone ones venturing out (late-February 2023).

Belonging to the phylum Mollusca, they are soft bodied with a thin internal shell.[i]

While they mainly get around by crawling on their foot, they can swim using wing-like flaps called parapodia, which most of the time are folded across their backs.

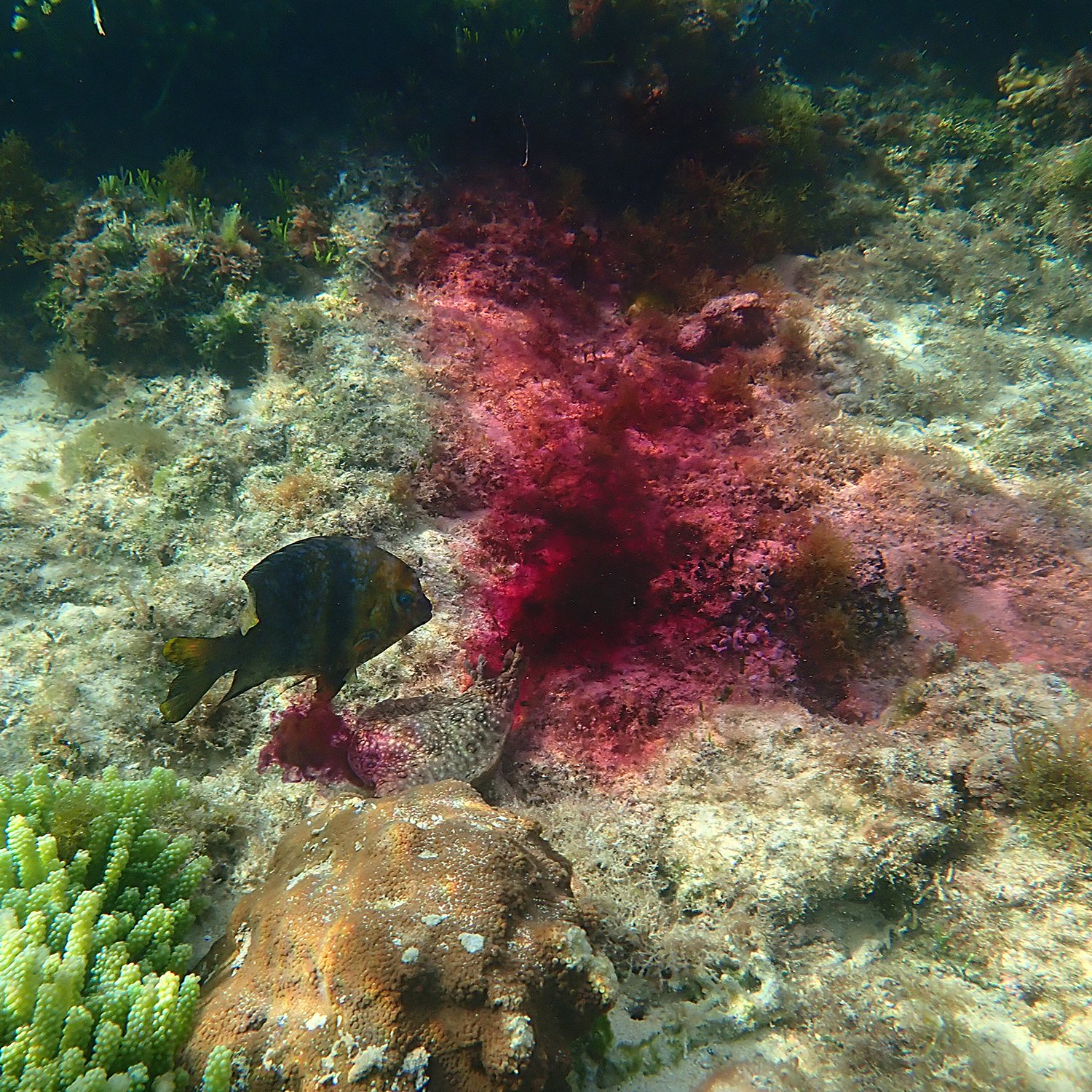

When attacked they release a purple dye. I once watched as a banded scalyfin (locally called an aatuti, Parma polylepsis) tried to take a bite out of one; it was certainly put off by the purple haze that came its way! (See images, below.) Interestingly, researchers have discovered that sea hare ink has antibacterial properties.[ii] They don’t synthesise this dye themselves, but instead it comes from the algae they eat.

Their other defence mechanism is that they produce a toxic slime. So if you do pick one up, wash your hands. And don’t let your dog eat them.

White-speckled sea hares can reach a decent size, usually around 20 cm or so, but I have seen a couple of larger ones that would have to have been about 30 cm.

They are hermaphrodite – both male and female – and in the early autumn you will often get together in chains of two or three (the number in the chain can depend on their density in a particular environment). I have seen as many as five of this species mating together in Emily Bay. They will assume the role of female to the one behind and male to the one in front.[iii]

Their eggs look like little piles of spaghetti. I’ve seen both yellow and orange ones, presumably from different species of sea hare. (See photo below.)

When they die, they often do it en masse after mating and laying their eggs. We had quite a few die in May 2022 in the channel area between Slaughter and Emily Bays. (See photo, bottom.)

They live about 12 months or so.

The white-speckled sea hares get confused with Aplysia dactylomela (which live in the Atlantic Ocean); they are a distinct species.[iv]

Their appetite for algae makes these another really useful species to have in our bays, along with parrotfish, sea cucumbers and sea urchins. Because of that, I’m looking forward to their return. I also I think they really are rather appealing in their own peculiar way!

In the video, below, two white-speckled sea hares are mating. Sea hares are hermaphrodites, with both male and female parts. The penis is on the right side of the head while the vagina is in the mantle cavity, which is between the parapodia (those wing-like structures).

Therefore, they can switch between being either the male or the female when mating (but they can't fertilise their own eggs). In this video, the one approaching and subsequently on top is acting as the male.

Sea hares dying, en masse (May 2022)