Three years ago, on the morning 31 July 2020, we woke after a night of torrential rain to a scene of devastation in Emily Bay on Norfolk Island. It is not something I will forget in a hurry. Arguably one of the most beautiful bays in the world was a fetid, smelly mess caused by the raw sewage that had flowed from the poorly maintained sewerage works and private septic tanks, down the hill and into the bay.

That day I was galvanised into action. Since then I have been raising awareness about the wonders of our reef and agitating for better management of the water quality that flows off the island and onto it. There have been plenty of reports and research done, and some small improvements made, too. But really, we have only nibbled around the edges of the problem. The elephant is still firmly in the middle of the room, as I explain in the article.

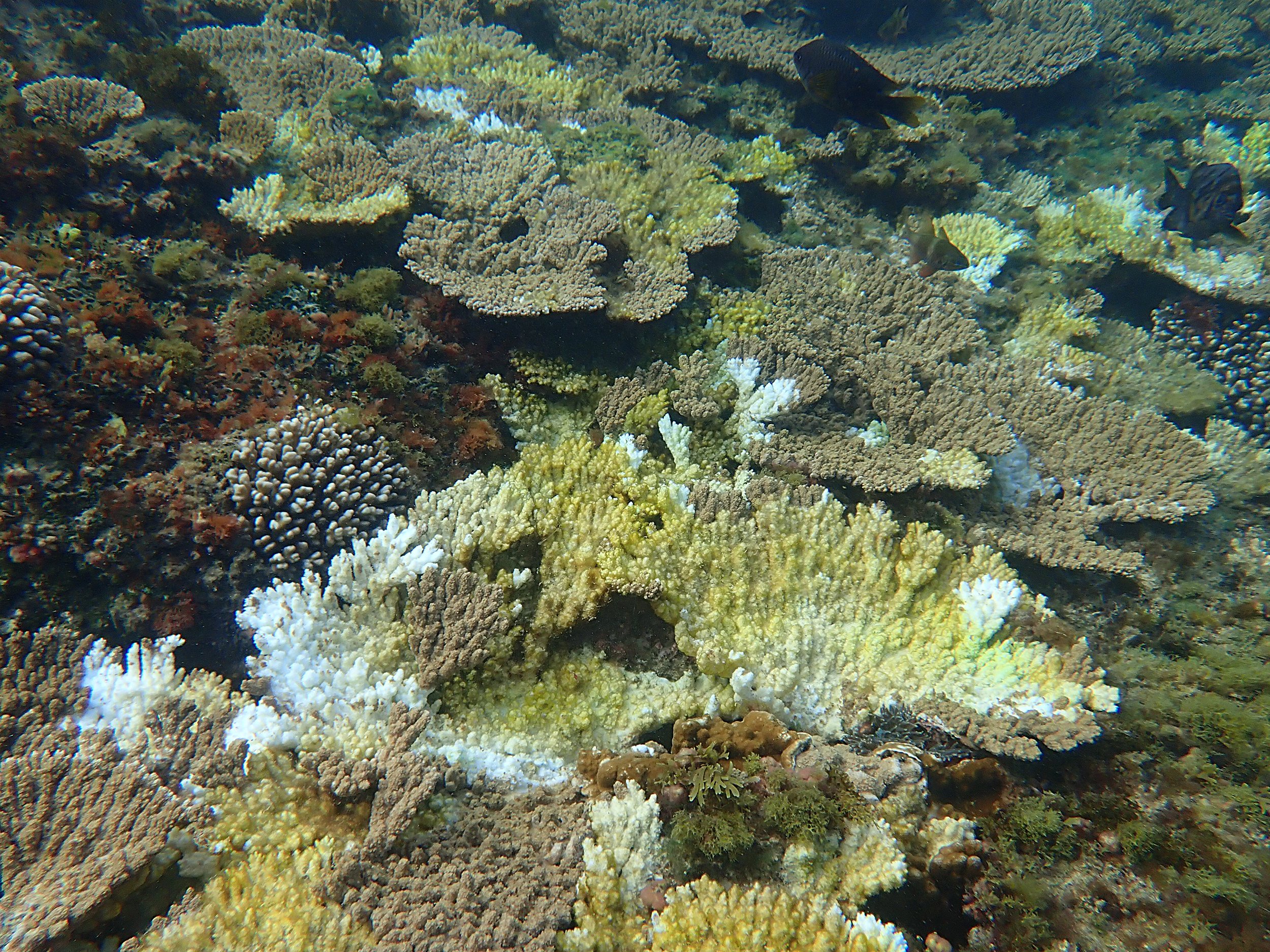

Each day I swim, I see new outbreaks of coral disease and algae taking over.

The clock is ticking for our reef.

Above: algae, dead and dying corals and disease are prevalent on the reef.

The importance of wetlands to reefs

As humans, we are intimately connected to our environment, and our environment is intimately connected to us – it is an elaborate network of interdependency. In 1971, environmentalist Barry Commoner coined the ‘Four Laws of Ecology’:

everything is connected to everything else

everything must go somewhere

nature knows best

there is no such thing as a free lunch.

These are worth thinking about as we grapple with the competing issues and stakeholders surrounding Norfolk Island’s reef, including the protection of the convict-era settlement buildings, which are part of a World Heritage property, the traditional cultural land uses of the area, and changing weather patterns.

But grapple with the issues as we may, the bottom line is that our reef is suffering; moreover, we know it is suffering. It is no longer in the realms of gut feelings and hunches. This is what the science is telling us. We have diseased corals and an increasingly algae-dominated reef and just ignoring it won’t make it go away.

In the final analysis, though, it’s really quite simple; the end game is that Norfolk Island’s coral reef is the first line of defence to protect our World Heritage area of Kingston and Arthur’s Vale, one of the eleven historic sites that form the Australian Convict Sites World Heritage Property, from inundation by providing a buffer from any potential and anticipated sea-level rises, and from the powerful storms and surges predicted with the changing weather patterns to come.

And the Kingston wetlands are our last line of defence to protect Norfolk Island’s reef.

Without a healthy reef, protecting Kingston will become an engineering nightmare, and that doesn’t even begin to address the dollars it will cost. Of course, the loss of the reef means a lot more than losing Kingston. We are talking about the loss of biodiversity and possibly as-yet-unidentified species, alongside all its associated cultural and social values, and recreational amenities.

Tourism on Norfolk Island is thriving. Tourists come here for many reasons, including for the island’s natural beauty, for its intriguing, multi-layered history, to meet the direct descendants of those most famous mutineers of all time – from the Bounty. And to enjoy being emersed in unspoiled natural surroundings. Norfolk Island’s beautiful little reef is right up there with the things they come to see. Reefs are, after all, a source of wonder for many, and understandably so.

Ergo, the loss of Norfolk Island’s reef has far-reaching impacts, and not only for Norfolk Islanders – for the world, too. We will all be the poorer.

Each time I go swimming, which is most days, I record what I see. Increasingly I come back with more photos of new cases of coral disease outbreaks than anything else. I’ve given up trying to monitor all the new outbreaks I see. It’s not pretty.

To explain the problems we face and where we go from here, I thought I’d recap on a number of my previous articles, and at the same time address some of the misinformation around wetlands and their role.

A little history

I cover much of the history in the article ‘Draining the swamp’ on this blog, but here’s a summary.

Corals dislike fresh water. They dislike nutrient-rich fresh water even more. When the coral reef formed millennia ago, there may have been pulses of fresh water going into the lagoons, but not the steady inundation that there is today, as I will explain.

1788 map by William Bradley showing the coastline of Kingston and Chimney Hill before it was quarried.

*Norfolk Island ; S. end of Norfolk Island / W. Bradley delin. 1788 ; W. Harrison & J. Reid sc

King’s channel became silted up after the settlement closed in 1814. When it was reopened in 1825, the original channel was restored and further drainage works were undertaken. Wakefield’s 1829 plan shows the now-restored first channel as it passes to the north of Chimney Hill before emptying into Emily Bay.

*Plan of the settlement and Garrison Farm & Co., Norfolk Island / surveyed by Capt. Wakefield, 39th Regt., May 1829

Before the British arrived and drainage channels were cut through the swamp, and Chimney Hill hadn’t been quarried, Chimney Hill created a natural, continuous stone barrier from where the lime kilns are, right across today’s road that now allows access for cars and pedestrians to Emily Bay (see the lefthand image, above). This rock formation effectively prevented fresh water draining into Emily Bay in large volumes. Instead, water pooled in a swamp and trickled out to sea via the underground water table. Presumably, when there was a particularly huge inundation, the swamp would have expanded, with the water spreading across what is now the golf course and made its way out to sea that way as well. It is also worth noting here that this water didn’t contain the pollutants and nutrients that it does today.

One of the earliest engineering works to be undertaken in the colony – indeed in either of the new colonies of Port Jackson (Sydney) or here – was to cut a channel around the north side of Chimney Hill (to the south of Government House), which then took a sharp turn south and into Emily Bay (see the righthand image, above, which clearly shows this first channel at a later date). Part of this original channel, constructed in 1789, can still be seen near the stone steps that were created during the later British Penal Settlement just near where the creek flows out into the bay.

When the settlement was abandoned in 1814, the channel filled up with sediment and the wetlands reformed. Nature has a way of reclaiming her own. Remember Commoner’s laws of ecology? Nature knows best.

Early in the British Penal Settlement (1825 to 1856), the channel around Chimney Hill was cleared of this built-up sediment so it could drain freely once more. This measure sufficed to drain the swamp for a time, allowing agricultural pursuits and building work to take place. However, in 1834, after a particularly severe flood, Major Anderson had a straighter tunnel constructed directly through the heart of Chimney Hill, rejoining the original channel before it entered the bay. The original channel to the north of Chimney Hill was filled in.

Chimney Hill was extensively quarried in the 1840s, which then allowed easier access to Emily Bay from the other parts of the settlement.

A catalyst for further modifications to the channel drainage system occurred in 1936, after an unprecedented flood put the Kingston Common and Golf Links underwater. Between 1939 to 1942 a new drain was dug, bypassing the channel going through Chimney Hill and instead draining directly into the bay. This drain functioned until 2015. That year, Dr Kellie Pendoley had voiced her concerns that the reef had five to ten years until it was wiped out. I believe she is on the money. Consequently, it was filled in in order to prevent too much freshwater flooding the coral reef.

The creek running into Emily Bay today

Droughts and flooding rains

Another of Commoner’s laws was that ‘everything must go somewhere’. And indeed, it must.

In early 2020, the island’s record-breaking drought broke reasonably gently. With the advent of a strong La Niña weather pattern, on the night of 30 July 2021, we had heavy rains resulting in torrents of smelly, nutrient-rich (for that read ‘polluted’) water flooding the bay. With devastating effects to our reef.

I immediately raised the issue with the authorities, but it wasn’t until a year later that I finally plucked up the courage to come out publicly and explain what had happened in an article called ‘The state of play on Norfolk Island’s reef’:

According to a Norfolk Island Regional Council’s (NIRC) Facebook post on 2 August 2020, issued after that rain event, the count for thermotolerant coliforms (also called faecal coliforms) entering Emily Bay was greater than 1,000,000 CFU/100 mL (more than 6,500 times the acceptable limit). To put that in perspective, according to NDTV on 26 May 2019, the highest faecal coliform count in the River Ganges was found at Khagra in Berhampore in West Bengal where it was 30,000 MPN/mL (one MPU is equivalent and interchangeable with one CFU), which is twelve times greater the permissible limit and sixty times greater than the desired limit (in West Bengal).

Let me just repeat that in simple words: the faecal coliform count for the waters of Emily Bay was more than 6,500 times the acceptable limit.

In November 2020, it happened again. The stress caused to the corals in the bay was dreadful to witness. Anecdotally, fish left the lagoons in significant numbers.

In that article, I listed a few of the many reports we have, going back to 1966, warning us about the issue of poor water quality running onto our reef and the detrimental effects this was having to it.

The algae in the bay reacted as any good self-serving and resourceful organisms would do – by proliferating. Since then, we’ve experienced an ongoing cycle of algae blooms in the water columns, mats of slimy cyanobacteria (lyngbya) and green turf algae, and verdant coverings of Caulerpa algae, among others. It’s thought that some of these are toxic algae, which caused the green sea turtle Doris to develop soft shell disease after eating them. It’s why we have had warning notices placed in our media telling us not to touch the lyngbya while swimming. And it is why we have notices up at the entrance to our seashore area warning us not to swim after heavy rain.

Algae are faster to grow than corals, out competing them for space. As a consequence, the reef has been undergoing a phase shift, which I write about here, in ‘Phase shifts and biodiversity’.

With the best of intentions, in 2021, leaky weirs were installed in the channel, slowing overland water flooding into the bay, and as a consequence the wetlands gradually began returning to its pre-ordained, natural state. I believe some of these weirs have now been removed, which in itself can cause problems when high spring tides send saltwater running back up the creek into the wetland. But that is a whole different issue.

And that is where we find ourselves today.

Why do we need wetlands?

I thought it was worth explaining the advantage of having properly maintained wetlands. Around the world, wetlands have been under-appreciated and consequently we’ve been quick to drain them.

According to the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water:

Wetlands are a critical part of our natural environment. They protect our shores from wave action, reduce the impacts of floods, absorb pollutants and improve water quality. They provide habitat for animals and plants and many contain a wide diversity of life, supporting plants and animals that are found nowhere else.[i]

Emily Bay full of sediment after heavy rain in July 2022

Worldwide they are recognised as being a vital part of a healthy environment. There is a convention to protect those that are of international importance – the Ramsar Convention. As the website says, they are considered to be ‘vital for human survival. They are among the world’s most productive environments; cradles of biological diversity that provide the water and productivity upon which countless species depend for survival.’

Our little wetland may be tiny but it is no different.

The simple fact is that coral reefs and wetlands are interconnected (remember another of Commoner’s laws of ecology – everything is connected to everything else), just as we too are connected. Nothing exists in isolation. A wetland is a valuable asset to any coral reef.

But we can’t talk about Norfolk Island’s wetlands without first thinking about the acid-sulphate soils that are found there.

Acid-sulphate soils are present in the lowland areas of Kingston where they have formed naturally over millennia, and if kept undisturbed and oxygen free (as in, kept covered in water) they are harmless. According to a Queensland Government site on the topic, Acid sulphate soils explained:

If acid sulfate soils are dug up or drained they come into contact with oxygen. The pyrite [that is] in the soil reacts with the oxygen and oxidises.

This process turns pyrite into sulfuric acid, which can cause damage to the environment and to buildings, roads and other structures. [Emphasis added.]

The acid also attacks soil minerals, releasing metals like aluminium and iron. Rainfall can then wash the acid and metals from the disturbed soil into the surrounding environment. [Again, emphasis added.]

Like everyone, and especially the tourists, I love our free-roaming cows. If I pop a photo of a cow grazing on the roadside on my social media page, it all goes a little bonkers. People love the idea that these beasts have right of way, and let’s admit, they are very photogenic. Allowing cattle to graze in the wetland environment has directly led to a situation where the acid sulphate soils have been disturbed. The pugging of the cattle’s hooves has introduced oxygen into the soil, causing a chemical reaction that has created sulphuric acid – battery acid. Cycles of wetting and drying have exacerbated the situation to the point where the best recommendation is to remove the cattle from that area and allow the water to cover and protect the acid sulphate soils.

It is this acid that has done much of the damage to the bridge’s foundations. I find it hard to believe that with modern engineering techniques we can’t find a solution to restore this precious architecture. In the back of my mind, I recall that in 1968 we were able to remove the World Heritage listed temple of Abu Simbel in Egypt to higher ground to save it from the rising waters of the newly built Aswan Dam. Our Bounty Bridge really is engineering small fry by comparison!

So from the acid sulphate soil perspective alone, we need those wetlands to stay.

But the reef was fine before the wetlands returned, wasn’t it?

Not really, no. Remember another of those laws: ‘there’s no such thing as a free lunch’. So while we thought we were gaining agricultural land by draining the swamp, we were also beginning to lose something else – the reef, albeit we didn’t realise it at the time.

As I’ve already mentioned, corals don’t like fresh water, and once that channel was cut under Lieutenant King’s instructions in 1789 allowing fresh water to inundate the bay, the die was cast and the decline of Norfolk Island’s reef began. Imperceptibly and slowly, the seeds were sown. So slowly no one would have recognised it even happening. I talk about a phenomenon called shifting baseline syndrome in my article ‘Portrait of a slow death’. Anyone who is new to our reef will be thrilled at how beautiful parts of it are. But they won’t realise what was there before and what it should really look like.

In the late 1990s, when I first began swimming the reef, an underwater camera was out of my price range, let alone the costs associated with developing the film. Today I’m able to take thousands of photos of the same coral colonies, over and over again. With a bit of effort put into sorting and cataloguing, I now have the beginnings of a useful resource that can show us exactly how much the reef has deteriorated in the last few years alone. This is the only way to conquer shifting baseline syndrome. As they say, the photographs don’t lie.

But like compound interest (interest paid on interest) the decline in the health of the reef has gradually gained momentum (diseased and dying corals added to diseased and dying corals) to the point we are at today where the situation on our reef is critical. As I’ve said in an earlier article, ‘Coral reefs are reasonably resilient but gradually, over time, the health of the reef has deteriorated, the damage compounding to the point where the system becomes unstable and a tipping point is reached.’

Septic tanks and soakage trenches

Remember another of Commoner’s laws: everything must go somewhere.

Unfortunately, we have contaminated groundwater, principally caused by the ongoing use of septic tanks and soakage trenches. Of the approximately 1,000 tanks installed on the island, Norfolk Island Regional Council believes as many as a quarter are failing, although I have seen reports that claim as many as 50 per cent, and that most would not satisfy the required setback distances from waterways and boreholes. Of these 1,000 septic tanks, about 220 are in the Kingston catchment (this does not include the ones in Kingston itself, which are currently being sewered). This equates to 67,800 litres going directly into the Kingston catchment and out into the bays.

We know, for example, that optical whiteners – found in laundry detergents and toothpaste – are flowing into our bays. If our septic systems were doing their job, this shouldn’t happen.

By their very nature, soakage trenches are designed to drain, so even a well-maintained septic tank in a poorly located area is polluting the environment. The connectivity of the aquifers means that septic systems across Norfolk Island could be contributing to the contaminated groundwater. Meaning that the 220 septics in the Kingston catchment are only the tip of the iceberg.

At the last census in 2021 there was an average of 2.2 persons per house. There are about 1,000 houses. The average water consumption is 140 litres per person per day. This equates to approximately 308,000 litres of untreated effluent entering the environment daily. More than double the volume collected by the water treatment plant.

I believe we are going to need outside assistance to help fix the issue of upgrading our septic tanks. Even if every island home replaced its septic tank and soakage trench with an enclosed system (which, incidentally, would provide a supply of potable water for times of drought), it could take as long as twenty years for the water table to be pronounced ‘clean’. But that is no reason not to get started with the process. These are expensive pieces of infrastructure for the average household to replace, but could we look at schemes where these systems are purchased in bulk, or where interest-free loans are available, or the waste-management levy is waived? If you do the maths, it would still be cheaper to replace every single system on the island than to install a piped sewerage system.

We can help too – by being careful about the pesticides, fertilisers and cleaning chemicals we use in our gardens and homes. Eventually, everything that runs from our sink or shower will end up in our marine environment.

Let’s allow 2,000 people to defecate on Kingston’s common, everyday

In a previous article, I referred to the rather unhealthy pong associated with the wetlands (‘Tiptoeing through the government silos’). It’s a fact that each cow on the common produces as much as 29.5 kilograms of excrement per a day. Imagine you have 20 cows grazing there (and there are often more). That is like allowing 2,000 people (who each produce on average around 300 grams of excrement per day) to all defecate on that pasture at one time. Twenty cows creates more than half a tonne of poo a day, which inevitably filters through the waterways and out into the bays. Every day.

Which begs the question, why do we allow this to happen?

Cows enjoying roaming freely through the wetlands. This water runs directly into Emily Bay

What does a wetland do?

A wetland is a natural filter, removing nutrients and sediment from the water before it discharges into the ocean.

A wetland is a wonderous thing. If allowed to work correctly, it is a natural cleaning filter. Water quality tests by CSIRO have shown that the Kinsgston wetland is beginning to act as it should, as a filter, naturally improving the water quality that is flowing out onto our reef. The wetlands prevent sediment (which is so destructive to coral reefs) from escaping. And the wetland’s vegetation uses the excess nutrients in the water to grow, thereby purifying the water.

At the same time, it is a unique habitat for birdlife. Already our social media pages have been filled with thrilling new observations in the wetlands. In and around the wetland’s waters reside some amazing creatures: long and short finned eels, snails, crustaceans and crabs. There are plant species that could make a comeback too. How many people know that the melky tree (Excoecaria agallocha) is a member of the mangrove family? A few of these hang on, clinging to the hillside above the Cemetery.

Conclusion

I have consistently reported on what I see happening under the waves, and it isn’t good. We need to make some changes soon if we want to save our reef.

The ‘water quality/reef environment/wetlands/World Heritage’ nexus is a series of complex and wicked problems that won’t be solved overnight. A thoughtful, steady hand, willing to follow the best scientific advice, even if that means going against popular opinion, is what is needed here.

We would be wise to heed the advice that the scientists are providing, after all, it is we who asked them for that advice in the first place.

Commoner got it right with his ‘Four Laws of Ecology’:

everything is connected to everything else

everything must go somewhere

nature knows best

there is no such thing as a free lunch.

As I said at the beginning of this article, in the final analysis it is quite simple. Norfolk Island’s coral reef is the first line of defence to protect our World Heritage area of Kingston and Arthur’s Vale, and the Kingston wetlands are our last line of defence to protect Norfolk Island’s reef. Let’s hope that in three years time there will have been some decisive action to help save our reef.

[i] https://www.dcceew.gov.au/water/wetlands/about, accessed 1 August 2023.