August is the coldest month of the year in the water, here on Norfolk Island. And not only do swimmers turn a little bit blue (if they stay in too long), so too do some of the corals.

But before we look at that, here is a brief summary of Coral 101:

corals are animals that live in a mutually beneficial (symbiotic) relationship with a type of microalgae called zooxanthellae

the zooxanthellae photosynthesise and provide organic carbon (energy) to the corals, and receive inorganic nutrients (fertiliser) from their coral hosts

corals are sensitive to small changes in water temperatures – long periods of higher temperatures result in the breakdown of the coral–zooxanthellae relationship, and if warm for long enough, will lead to coral death

coral bleaching occurs when the zooxanthellae leave the corals – without the nutrients provided by the zooxanthellae, the corals eventually die of starvation and disease.

Having said that, when the zooxanthellae leave the coral the coral doesn’t always starve and bleach permanently, as I will explain.

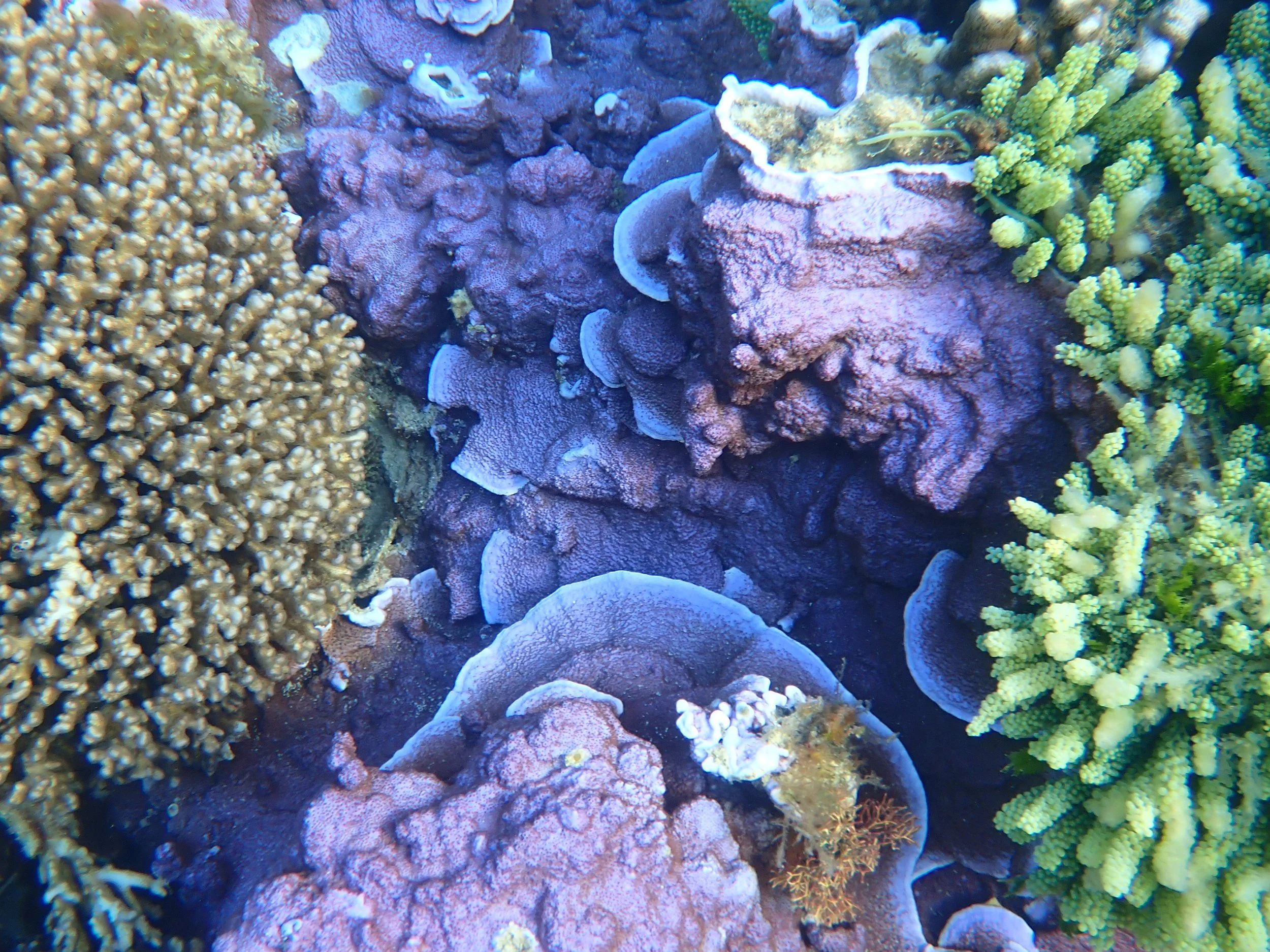

Norfolk Island has the second most southerly reef in the world after Lord Howe, so our corals are used to cooler temperatures. Through September of last year – so late winter into early spring – I recorded some of them changing from a brown to a brown–purple, to a much more deep and dramatic blue–purple over the space of a few weeks.

It is almost that time of the year again, because this week I noticed a couple of colonies start to colour up once more.

I asked Associate Professor Tracy Ainsworth, a coral expert who has undertaken research in Norfolk Island’s lagoons, if this blue colouration is ‘normal’.

This was her response:

‘The blue coral – gorgeous. You guys have some fascinating and different corals there. If it goes blue in winter and spring, it’s probably just the normal population changes in the symbiotic algae in the tissues. The blue of the coral itself is more visible when there are less green–brown algae inside the tissues.

‘In winter this coral likely relies on filter feeding and less on photosynthesis, so the algae population reduces. It could be because its cold and the algae don’t grow as fast, or just that there is a lot of plankton for the coral too feed on and they are able to keep the numbers of algae lower.

‘It’s fascinating and rare.’

Only some corals change colour this way. Below is a compilation of images from September 2020, and below that a couple of images of the coral beginning to change this year. Can you see which coral colony of these bottom two photos also features in the compilation from last year?

Corals photographed through September 2020

Other pleasing captures this week included two lovely wrasse that I always find difficult to photograph because they move so fast:

a gorgeous moon wrasse, Thalassoma lunare (top left image); I’ve also included a few photos of this colourful little wrasse so you can see the colour variations

and a redspot wrasse, Stethojulis bandanensis.

Both of these were hanging around at the far end of Slaughter Bay, near the Kingston pier.